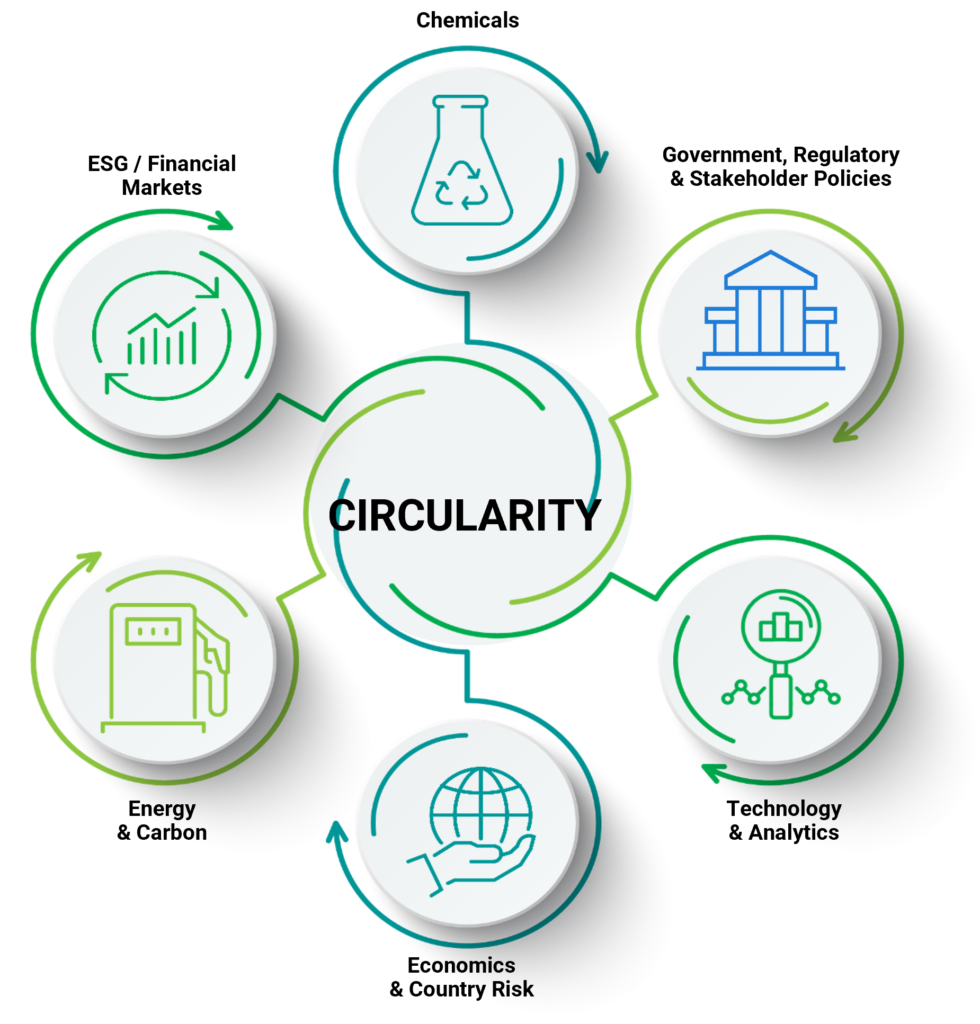

Comprehensive Analytics and Insight for the Plastics Value Chain’s Transition from a Linear to a Circular Economy.

The service addresses the implications of carbon intensity and the impact on future capital investments within the context of energy transition and carbon valuation, amid changing policies and regulations.

This service quantifies the magnitude and timing of substantial market shifts, identifies key regulatory and societal risks, and provides ongoing tracking of fast-moving developments. Clients will understand the potential impact of costs, investment, and emissions of the linear and circular plastics models.

Moving to a Circular Economy

The plastics ecosystem is firmly in a transition where companies design out waste by keeping resources in use as long as possible and extracting the maximum value while at that. It is followed by recovering and regenerating valuable products and materials at the end of life. This transition occurs within the broader structural shifts of the energy transition as fuel demand peaks, raising the plastics demand risk profile and bringing forward challenges to balance emissions with the circular plastics end-of-life goals.

Gain a Tactical Advantage and Reformulate Your Company Strategy

Attain essential insight and analytics for the tactical oversight of your business as well as the reformulation of your company strategy around the transition from linear to circular value chains:

-

Track government regulations, policies, and targets established by brand owners, industry alliances, NGOs, and ESG investors and understand what this means for your business in the countries and regions where you have operations

-

Prepare a plan to mitigate against major sustainability-driven shifts in downstream plastics consumption

-

Determine how to position product offerings as increasing amounts of recycled content become available.

-

Assess opportunities for collaboration and investment in the plastics transition to circularity

-

Assess the relative value propositions of competing recycle technologies and anticipate where investments will be directed to scale infrastructure.

-

Anticipate the timing and magnitude of the impact on feedstocks that will develop during the plastics transition to circularity.

These Key Questions Include:

|

How do companies understand and sort through the complex interplay between production and recycling economics, emissions, societal needs, and resources? |

|

|

To what degree and at what pace will post-consumer recycling infrastructure and technology scale and accelerate to meet targets? |

|

What is the potential for any unintended consequences of regulations and policies along the entire value chain? |

|

|

How will the economics for circularity develop, and what role will policy play? |

|

|

How do companies define their competitive position in a circular environment? |

Service Insight and Analytics

A summary report summarizing key developments from all modules across the circular plastics landscape focusing on “What Has Changed” during the prior period as well as periodic podcasts and focus pieces.

Frequency/Format: Quarterly

A comprehensive, global policy database of Plastics Regulatory, Policy, and ESG activity with accompanying insight.

Frequency/Format: Monthly Updates

Scenario demand modeling, visualization, and insight for virgin and mechanically recycled plastics with regional and end-use segmentation

Frequency/Format: Updated twice per year

Scenario modeling and insight for collection and disposition of plastic waste via landfill, incineration, mechanical recycling, and chemical recycling. Analyses of plastics waste supply including categories, volumes, specifications & quality requirements.

Frequency/Format: Updated twice per year

Technology scanning and scenario-based economic modeling for recycling technologies. Database of recyclers’ capacities, alliances, inputs & outputs, and facilities commercialization progress.

Frequency/Format: Realtime database updates with scenario updates twice per year

Scenario-based modeling and insight to evaluate the economics and emissions for circular plastics production compared to the incumbent, fossil-based linear model for producing plastics.

Frequency/Format: Updated twice per year

Strategic conclusions derived from the detailed study analyses targeted at identifying risks, investment opportunities, infrastructure needs, and recommended positioning & actions for industry participants.

Frequency/Format: Updated twice per year

Benefits of the Service |

Application by Customers |

|

Anticipate future recycling volumes under different scenarios |

|

|

Quantify the timing and magnitude of impact on feedstock markets |

|

|

Understand different regulatory regimes and track and anticipate changes globally |

|

|

Compare competing mechanical /chemical process technologies and understand which may prevail |

|

|

Evaluate the level of societal demand in different markets |

|

|

Technology development trends |

|

|

Understand which chemical and plastics companies might prevail |

|

|

Calculate carbon emissions and unit costs based on different infrastructure types |

|

Talk to an Expert Schedule a Demo